Oliver Wyman, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, has undertaken a groundbreaking study of the consumer health information landscape. In partnership with Altarum Institute, Oliver Wyman is exploring the health information needs of consumers – particularly low-income, uninsured, and non-English speaking individuals, and their caregivers. To assess stakeholders’ perceptions of these consumers’ needs, as well as organizational priorities and investments, Oliver Wyman recently conducted interviews with nearly 100 senior leaders from across the healthcare marketplace. The findings indicate that while marketplace stakeholders recognize the value of providing health information to vulnerable consumers, no one has “cracked the nut” of doing so. And though stakeholders recognize that the health information they currently provide does not adequately enable consumers to make informed healthcare decisions, they see barriers to providing effective health information at every level of the healthcare system. Read the full report for more information about current health information efforts and perceived barriers. Here, Oliver Wyman Principal Graegar Smith, who led the project, shares four additional findings and strategies:

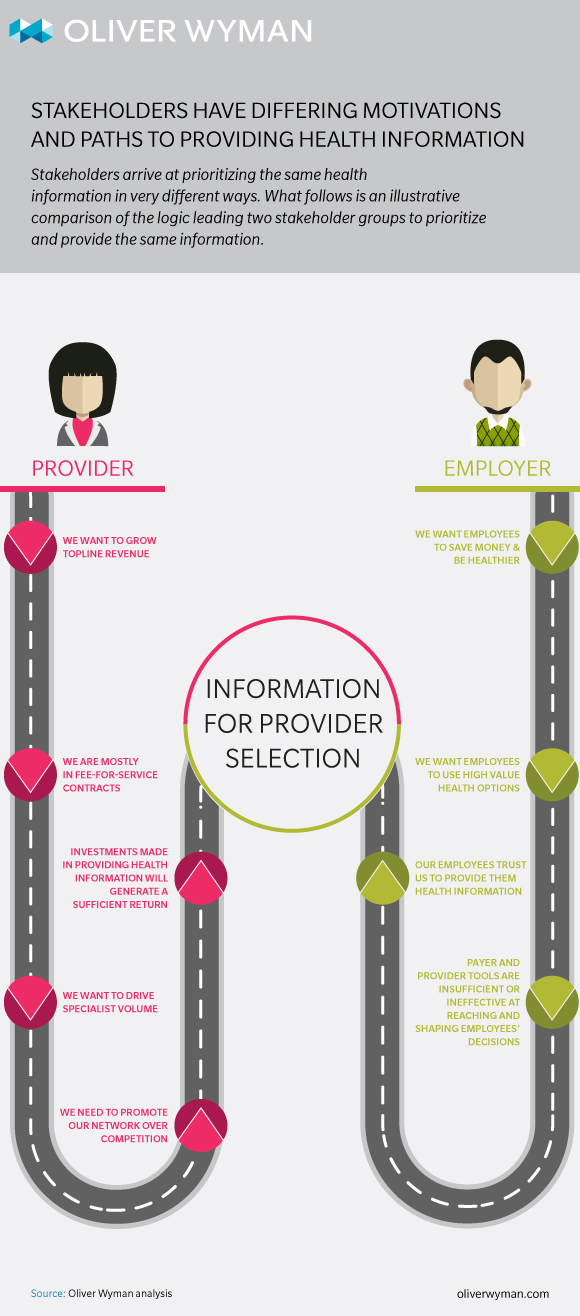

1) Stakeholders need to be more clear about why they offer health information in the first place

Through our interviews, we found the vast majority of stakeholders are still in the developmental phase of their health information strategy for all consumer segments. Many are trying to define priorities and approach while they also work to understand how they will integrate a health information strategy with other higher-level strategic priorities. This state of development generally makes sense; this is an emerging space with no de facto approaches and innovation does not typically follow a straight line.

Nonetheless, we observed too many stakeholders approaching health information with unfocused and occasionally misdirected approaches. For example, some of the stakeholders we talked to had portfolios of health information offerings; but when asked about why certain offerings existed, they could not articulate a clear “reason for being.” The sense was that these things existed in some way, shape, or form in the past, and stakeholders simply repurposed them to be consumer-directed datasets or tools.

An example of this sort of “backwards thinking” is the patient portal. When designed and deployed incorrectly, it is an example of repurposing a system and data meant for one thing – in this case, clinical records management – without strategically thinking about the consumer action the stakeholder hopes to drive. That is, patient portals are primarily used as a transactional system – check a lab result, request a prescription refill, etc. And because they are limited by the functionality and scope of their original purpose, they miss the opportunity to achieve more, such as serve up additional wellness information or drive patient engagement.

No matter where stakeholders are in the development of their health information strategy, they must be thoughtful and strategic, and much clearer about what they want to achieve with their health information offerings. Only after they have defined the desired consumer action should they focus on how to drive it and how they will measure their own success.

Only after stakeholders have defined the desired consumer action should they focus on how to drive it and how they will measure their own success.

2) Proving outcomes and return-on-investment is a critical need

Nearly all plan, provider, and employer stakeholders we spoke to raised questions, if not concerns, about the return on investment (ROI) of health information. In their eyes, compelling data on the effectiveness of health information is limited; and without solid ROI data, organizations are hesitant to make further investments.

Commonly available metrics such as web traffic and call volume are suggestive, but lack the detail and outcomes impact that companies need to justify significant investment. What’s more, data gathering is complicated by the fact that many stakeholders are not clear about desired outcome, and so struggle to identify means to measure or define success.

What’s more, because so many other strategic initiatives do have solid ROI metrics and data, health information looks especially “soft.” For example, a Medicaid plan weighing the pros and cons of various strategic investments can see solid data and measurable ROI for a high-risk pregnancy care model. In comparison, investment in a more opaque consumer-facing health information strategy is a harder sell.

While individual stakeholders must work to overcome biases against health information strategies, the challenge is greater than that. The ecosystem as a whole must address this barrier. Better metrics and data will likely originate with the health information companies themselves, as they obviously know their offerings the best and have a clear incentive to prove the worth of such offerings.

But there is a risk these companies may be myopically focused on their individual information “domain” and that there will be an unnecessary proliferation of narrowly defined metrics. Consequently, providers, plans, and employers should take a more proactive role in defining the metrics important to them.

Providers, plans, and employers should take more proactive role in defining metrics important to them.

3) Greater attention and resources must be devoted to solutions for non-English speakers

More than one in five U.S. residents speaks a language other than English at home, and nearly 40 percent of the 55 million Hispanics in the United States mainly use Spanish. With today’s minority populations poised to become the majority population by 2044, understanding and meeting the needs of non-English speakers is becoming increasingly important.

Yet when asked about information sources and resources for non-English speakers, a significant number of stakeholders directly admitted or indirectly hinted at being underprepared. And the initiatives that are in place are, unfortunately, severely inadequate. For example, simply having access to a 24/7 language translation line is not a non-English speaking consumer strategy. Further, it is a misconception that someone that is able to speak English as a second language prefers to engage in their health and healthcare in the same way as someone whose first language is English.

Given the size of this population, it will have far-reaching impact on numerous aspects of stakeholders' business model. Payers, providers, and employers must reconsider everything from benefit design, network design, care models, care team composition, and (yes) health information strategies with this population in mind.

Understanding and meeting the needs of non-English speakers is becoming increasingly important.

4) Cross-ecosystem solutions need less duplication for greater success

Some stakeholders raised concerns about the duplication surrounding health information. That is, multiple stakeholders providing information on the same health need or topic. (For example, both employers and provider organizations offer information about locating providers.) This can lead to confusion and information overload in consumers.

At the same time, such duplication leads to wasted resources, when better coordination and integration could eliminate duplication and free resources for other efforts.

Further still, if a stakeholder thinks exclusively about their own situation and use case, and not those of other stakeholders that could be complementary or competing, the end result could be suboptimal. For example, a payer might design its health information offerings thinking only about its objective – a great benefits website. Meanwhile, a provider might create a consumer-friendly list of “rack rate” pricing for different tests or procedures. Both are designed with the consumer in mind, but don’t actually integrate the consumer experience. A more impactful offering would be integrating those two functionalities such that a consumer could know what a test or procedure would cost under their specific benefit plan and how it relates to progress against their personal deductible. Both stakeholders’ desired consumer action is incorporated into the strategy, and both benefit from a more robust and likely-to-be-used offering.