Efforts are underway to fight the opioid crisis. One missing component? The prescribing habits of doctors.

Meet Physician #1. Let’s say there’s one physician who really takes her time to educate patients on what pain level they should expect after common surgeries. She explains to them how to ladder Tylenol and Ibuprofen to manage pain. Maybe she even prescribes a few opioid pills here or there – with three specific instructions, that is: use them only if pain becomes unmanageable, use them sparingly, and dispose of them properly given their addiction risk and potential for abuse. The result? A typical patient leaves with a prescription for 5 opioid pills.

Meet Physician #2. Let’s say another physician (who’s practicing on the very same floor) has a different approach to opioids. He leaves the patient education component out of the equation, instead just handing over prescriptions right to the nursing staff to manage. Unlike Physician #1, he gets calls a couple times a week from patients who complain of ongoing pain. To avoid patient follow-up, he errs on the side of prescribing more opioid pills. The result? A typical patient leaves with a prescription for 30 opioid pills.

Meet Physician #3. A third physician (working in the very same building as the others) just uses the pre-filled hospital order sets with a typical dose of opioids following similar common procedures. Given the variation in perspectives among doctors and the desire for efficiency (they’ve developed a single order set for all patients getting this procedure), they just pick the highest number of pills a patient might need. Then, this prescription is automatically sent to the patient’s pharmacy to be easily filled. E-prescribing for the win. The result? A typical patient leaves with a prescription for 60 opioid pills.

What do these physicians all have in common? They don’t believe they’re delivering “bad” care.

As illustrated above, many factors go into the care a patient receives. We believe ensuring patients are getting the right care (and not too much care) is still the responsibility of the physician. Physicians have the clinical authority to dictate when care is right, or not right, for their patients. Yet, physicians estimate over 20 percent of all care delivery nationwide – at an annual cost of $265 billion – is unnecessary and potentially harmful to patients.

All three physicians above likely believe they aren’t part of these staggering statistics because they are delivering “good” care. It is only when each physician is presented with a report showing how his or her prescribing pattern compares to guidelines and to their peers that they have occasion to step back and question the default practices ingrained in healthcare. This type of unnecessary care spans surgeries, diagnostics, prescribing, and the like, across every area of healthcare.

Measurement and Monitoring

The only way to combat it? Bring more guideline-based, comparative measurement to help healthcare professionals identify where outlier practices exist so they can spur discussion, education, and the reinforcing mechanisms that cause broken default care patterns to be reviewed and changed.

Here’s an example, based on analysis from Practicing Wisely, a program developed by Oliver Wyman:

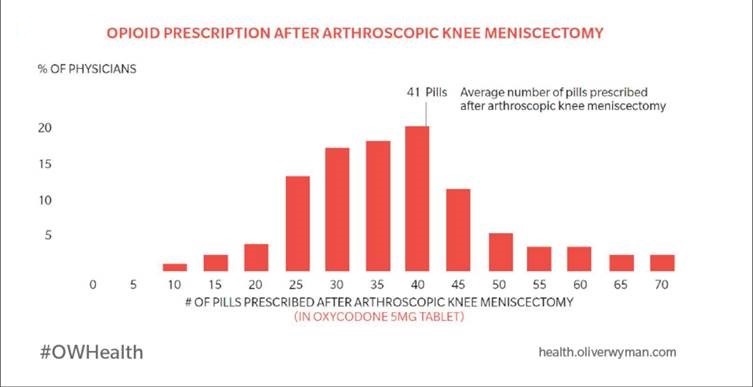

Although Appropriate Use Measure guidelines indicate fewer than 15 opioid pills are necessary, many orthopedic surgeons, for instance, prescribe an average of 40 pills to patients in their practice. Our initiative will hopefully curb the opioid crisis by reducing the number of pills that are legally, ever so easily, and far too often prescribed for some of the most common reasons people receive care. Pills that are incredibly addictive, destructive, and typically aren’t even needed in the first place.

This chart provides an interesting and even shocking glimpse into opioid prescribing habits. Consider, for instance, the number of physicians who regularly prescribe more than 40 opioid pills for a knee surgery, where solvethecrisis.org (a Johns Hopkins-affiliated program identifying recommended opioid amounts after specific procedures) recommends eight tablets (of Oxycodone, a 5 miligram equivalent) for an Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy or up to 20 tablets for an Arthroscopic, the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) repair. The fact that some orthopedic surgeons performing these procedures prescribe 50 or 60 or 70 pills is incredibly concerning variation. This lack of awareness among physicians in how their treatment choices differ from guidelines and peers is commonplace across the healthcare industry. Curbing the opioid crisis, and improving care across all areas of medicine, requires that we bring more visibility to individual physician performance (de-averaging performance analysis that shows overall hospital or medical group performance across a blend of medical procedures) and use peer-based variation analysis to help physicians understand how their treatment patterns differ from the average baseline. The opioid crisis is a stark example of how excessive care can destroy the lives of people who have sought the trusted guidance of a physician, when they're at their most vulnerable. Variation analysis can help physicians make wiser choices when caring for their patients. Necessary care, not dangerous care on autopilot, will save lives and improve care delivery.