Editor's Note: On March 19, three experts from our Health & Life Sciences team (Deirdre Baggot, PhD, RN, Bruce Hamory, MD, and John Rudoy, PhD) shared their insights with The Governance Institute. Although the coronavirus (COVID-19) situation and statistics are changing rapidly, the need for boards to take the long view while supporting management remains constant. We’re pleased to share this thinking here on Oliver Wyman Health.

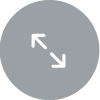

The COVID-19 pandemic has quickly grown from one concern among many to a dominant near-term societal issue. This situation accelerated so quickly and has taken so many by surprise. It’s now difficult to step back from the hour-by-hour, minute-by-minute reaction to the latest developments and plan for what needs may arise in a week, a month, or three months.

Our frontline healthcare workers are heroically managing whatever comes, and now it’s senior leadership’s job — including board members — to make sure workers have what they need in the coming weeks and months to effectively serve patients and ultimately mitigate the effects of this pandemic.

Senior healthcare leaders should be thinking about two major domains of activity: caring for the workforce and surge capacity planning.

Regarding the former, a frightened, distracted, and exhausted workforce will not make the split-second decisions and provide the rapid response the world needs right now. Caring for the workforce is also simply the right thing to do.

The latter, done right, will allow the system to deliver care as efficiently as possible, avoiding the disorganization and misallocation of resources that can lead to unnecessary delay, injury, and even death.

For doctors, nurses, and other clinicians, the truth is, this is what they are made to do. The very real and inspiring stories of heroism from healthcare workers across the world have already spread, and the expressions of support and gratitude from the broader community has been poignant. If there are any positives from this pandemic, a renewed faith in individual healthcare workers and the pride of teams who performed admirably under extreme pressure will certainly be among them.

However, the strains are undeniable. The day-to-day work of healthcare is getting harder. The pace is accelerating, and the work is becoming more dangerous and more difficult.

Life outside the healthcare facility is not easy either. Necessities of working life are growing scarce. School closures, for example, make working from home while caring for young children difficult. Viral videos of shoppers hoarding everything from toilet paper to milk make life less comfortable.

All of this basic societal disruption leads to fear, anxiety, depression, and exhaustion—at a time when we need the healthcare workforce to be performing at its peak. Leaders cannot flip a switch and make everything okay; this is a stressful time, especially for healthcare workers. But leaders can take actions that will support and reassure their teams. The remainder of this article provides several examples.

Caring for the Workforce

First, healthcare organizations must think creatively about how they can directly address the scarcities and life disruptions their workforces are facing. Health systems can work together to communicate how critical it is for cities to provide childcare options for healthcare workers when schools and daycares close, and continue to close.

New York City and San Francisco, for example, have kept some schools open to serve as critical sites for the children of essential workers. But many other cities have not done this.

When governments cannot provide a solution, healthcare organizations themselves should source their own childcare, erecting or renting facilities and staffing them with nonessential employees, or with temporarily assigned essential employees. The reasoning here is that it’s better to have one employee caring for multiple children than all employees caring for their children individually. Another idea is to match up idle or on-break college and high school students with needy parents to help tutor their younger children online, or formulating other creative solutions. Similar creative solutions can be explored to directly mitigate localized shortages of food and other items. Creative may mean imperfect, but this is not the time for second-guessing and dwelling on imperfections.

Even as healthcare organizations mitigate some of their workers’ anxieties, a general sense of unease and worry will remain for many. Leaders should ensure their teams are aware of and able to make full use of employee assistance programs to receive support as necessary. Even here, creativity may be necessary. Behavioral health professionals are in short supply in good times, and capacity may quickly be overwhelmed. This pandemic will peak regionally at different times; healthcare organizations may be able to smooth the availability of behavioral health workers by using telehealth to share capacity nationally and even globally.

Powering all of this will be frequent, consistent, and thoughtfully planned communication. Healthcare workers need to know the full reality of their work expectations and what specific practical and emotional support they can expect from their employers. Communications should be frequent, reassuring workers that leadership is engaged, but each new communication needs to be meaningful. Communications should be consistent; the board chair should not be sending one message while the system CEO sends another, while a local hospital administrator or department head sends another, all on top of messaging from the local and national health departments. Even if they are largely similar, small differences in content or language will create confusion and frustration. This is not to say that only one senior leader should be the voice. Line managers and other trusted local leaders should be deeply involved in communication, but should be armed with the right messages and words to reassure their teams on the ground. People are in need of information not only to learn, for example, about new operational updates or staffing changes as they arise, but to protect their health and well-being as new government restrictions come into play.

Powering all of this will be frequent, consistent, and thoughtfully planned communication.

Surge Capacity Planning

A cared for workforce is an effective workforce. An effective workforce will be necessary, but unfortunately not sufficient to manage the oncoming surge of patients. There are additional specific strategies that can help mitigate this surge.

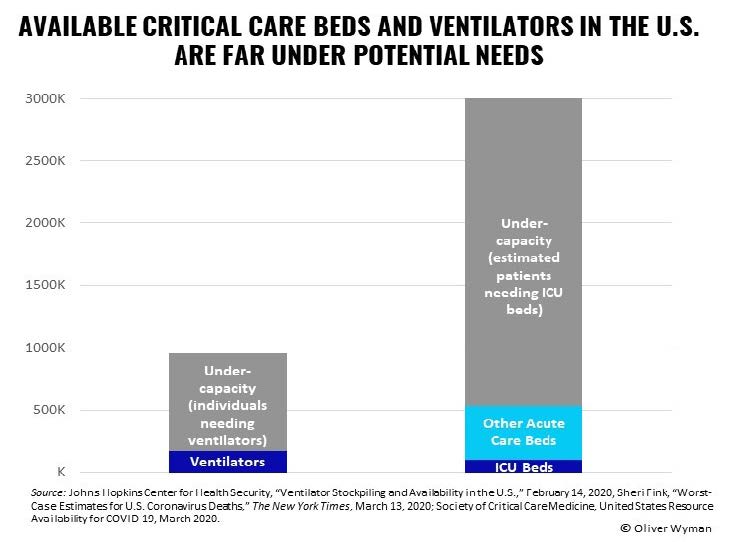

First, capacity planning for the COVID-19 pandemic must acknowledge there aren’t enough ICU beds, ventilators, or staffing capacity to manage the influx of patients. For example, the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security estimates there are 160,000 ventilators available in the U.S. for immediate use. Of these, about 62,000 are full-featured, and 98,000 have more basic features, but can be used in the current crisis. There are over 10,000 ventilators in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) strategic stockpile. Given that the 62,000 estimates for full-featured ventilators is based on a years-old study, there may be several thousand more than estimated.

However, CDC estimates suggest that close to a million ventilators may be needed to manage all those who become critically ill.

Optimistically, the extreme social distancing mandates that many localities are putting into place may help flatten the curve of COVID- 19 spread and ease burdens on capacity. However, it’s likely in many areas that capacity will be under severe strain. This calls for a central system capacity planning center staffed with individuals who have both the sophistication and the capabilities to use predictive modeling to anticipate capacity requirements over the next 30 to 60 days. And the power to bring extreme methods and resources to bear to address shortages.

This group must make several sets of decisions in the coming days:

- First, what functions and services can be temporarily eliminated to free up equipment, facility, and staff capacity?

- Second, to the extent that currently open capacity will be consumed as COVID-19 peaks, are there necessary procedures that need to be pulled forward when the capacity still exists

- Finally, are there vulnerable patients scheduled for elective procedures or even postponable necessary procedures that can be rescheduled to a time when healthcare facilities are more likely to be safer health-wise?

The planning group will also need to model scenarios of staffing availability, taking into account potential staff losses due to sickness, quarantine, or family responsibilities. As need surges, up to 20 percent of staff may be offline. Indeed, in early March, the Chinese government reported over 3,300 Chinese healthcare workers were ill with COVID-19. This is nearly double its last report of 1,700 in mid-February. In the U.S., the speed with which healthcare workers can go offline was demonstrated in Northern California, when 93 clinicians who had contact with one ill individual pre-diagnosis were forced into quarantine for two weeks, with two nurses ultimately becoming ill themselves.

Your organization should consider whether “exposed” staff members who are not ill could serve to care for patients in isolation, rather than remaining in quarantine themselves. Additionally, since it is difficult both physically and emotionally to “self-isolate” at home, allowing people to care for patients, and providing them housing in local hotels for the period of quarantine would serve two purposes — adding to your workforce and protecting their family and loved ones from further infection.

Healthcare organizations must craft an effective and empathetic message, ensuring everyone from physicians to receptionists can deliver it forward.

Even with effective capacity planning, given the surge in demand and the decreased numbers of available healthcare workers, there will likely be demand traditional capacity cannot meet. Hospitals will need to deploy new models for triaging patients and new sites for providing care, from temporary brick-and-mortar facilities that can triage and treat relatively minor issues offsite, to remote care delivery paired with take-home monitoring equipment that can allow higher acuity care-at home than is usually provided. In addition, organizations will need to take a careful look at their staff. For example, they can identify workers who may not routinely work in areas relevant to COVID-19 response but are still qualified or could quickly be trained to step in. This will require implementing new education modules and addressing compliance, union, and other barriers at uncommon speed.

All of this will need to come along with effective communication to affected patients. Those who are having procedures moved or postponed may be confused or frustrated, and those who seek traditional hospital care only to be diverted to home care, telehealth, or temporary sites may worry they are being deprioritized. Healthcare organizations must craft an effective and empathetic message, ensuring everyone from physicians to receptionists can deliver it forward.

There is no way to magically create capacity. But taking a proactive approach driven by predictive modeling and creative redeployment of capacity can take a potentially catastrophic situation and make it merely difficult.

These are complicated, often overwhelming times for healthcare systems. In these times, engaged boards that can help their organizations prepare for the long term will be especially critical.